The Olympic Games 1896 Athens

The Greeks are novices in the matter of athletic sports, and had not

looked for much success for their own country. One event only seemed likely

to be theirs from its very nature- the long-distance run from Marathon,

a prize for which has been newly founded by M. Michel Breal, a member of

the French Institute, in commemoration of that soldier of antiquity who

ran all the way to Athens to tell his fellow-citizens of the happy issue

of the battle. The distance from Marathon to Athens is 42 kilometers. The

road is rough and stony. The Greeks had trained for this run for a year

past. Even in the remote districts of Thessaly young peasants prepared

to enter as contestants. In three cases it is said that the enthusiasm

and the inexperience of these young fellows cost them their lives, so exaggerated

were their preparatory efforts. As the great day approached, women offered

up prayers and votive tapers in the churches, that the victor might be

a Greek!

The wish was fulfilled. A young peasant named Loues, from the village

of Marousi, was the winner in two hours and fifty five minutes. He reached

the goal fresh and in fine form. He was followed by two other Greeks. The

excellent Australian sprinter Flack, and the Frenchman Lermusiaux, who

had been in the lead the first 35 kilometers, had fallen out by the way.

When Loues came into the Stadion, the crowd, which numbered sixty thousand

persons, rose to its feet like one man, swayed by extraordinary excitement.

The King of Servia, who was present, will probably not forget the sight

he saw that day. A flight of white pigeons was let loose, women waved fans

and handkerchiefs, and some of the spectators who were nearest to Loues

left their seats, and tried to reach him and carry him in triumph. He would

have been suffocated if the crown prince and Prince George had not bodily

led him away. A lady who stood next to me unfastened her watch, a gold

one set with pearls, and sent it to him; an innkeeper presented him with

an order good for three hundred and sixty five free meals; and a wealthy

citizen had to be dissuaded from signing a check for ten thousand francs

to his credit. Loues himself, however, when he was told of this generous

offer, refused it. The sense of honor, which is very strong in the Greek

peasant, thus saved the non-professional spirit from a very great danger.

A large number of competitors had their names put down for this contest,

but most of them, doubting their strength had retired at the last moment.

Those competitors, who still clung to their purpose, to the number of 25,

went the evening before the day, appointed for the race to Marathon to

spend there the night They were accompanied by a special commission. On

the important day at 2 p. m. precisely they assembled on the bridge of

Marathon, from where they were to start. They were placed in one line,

each one at a certain distance from his neighbour. After a short allocution,

Colonel Papadiamantopoulos, who had been chosen starter, gave the signal

for starting by firing a revolver. The runners rushed forward, and off

they went accompanied by a troop of soldiers who had to watch the course

of the race. At some distance from one another several carts followed in

which medical men were seated, to be at hand in case of need.

Thousands of voices resounded inside and outside the Stadion, when

the signal announced the arrival of the victorious champion; it was in

vain to expect that the spectators should keep their seats. Everybody stood

up and all eyes were fixed on the entrance of the Stadion. At last the

chief commissioner of the police arrived on horseback and announced with

a loud voice, that Louis of Maroussi was coming. After a few minutes of

anxious expectations, the hurrahs resounding from outside the Stadion proved

that the victorious champion was near. All the officers and members of

the Committee rushed to the entrance to receive the victor, who entered

and continued running all along the right side of the Stadion till he arrived

near the seats of Their Majesties. The two Princes as well as the members

of the Committee ran at his side, waving their hats and joining in the

general rejoicing. Louis, although his features betrayed great fatigue,

was still bearing up well. His face was sunburnt, his white flanelsuit

covered with dust, thick drops of perspiration stood on his forehead, but

he kept on, running firmly, till he reached the seat of Their Majesties.

Here the Olympionic Victor was received with full honour; the King rose

from his seat and congratulated him most warmly on his success. Some of

the King's aides-de-camp, and several members of the Committee went so

far as to kiss and embrace the victor, who finally was carried in triumph

to the retiring room under the vaulted entrance. The scene witnessed then

inside the Stadion cannot be easily described, even strangers were carried

away by the general enthusiasm. When the Greek flag had been hoisted on

the mast at the entrance, the cheering continued in deafening shouts. Everywhere

small Greek flags were waved joyfully by the enthusiastic Greeks. Amidst

this general rejoicing, the first chords of the National Anthem struck

up and its strains found an echo in the heart of every true Hellene. Meanwhile

Louis was resting on his well earned laurels. He had made a run of 40 kilomètres

in 2 hours 58 minutes and 50 seconds. Some minutes after Louis, arrived

Vassilakos, whose arrival provoked another burst of applause. He had run

the same distance in 3 hours 6 minutes and 3 seconds.

Source document: Official Report 1896

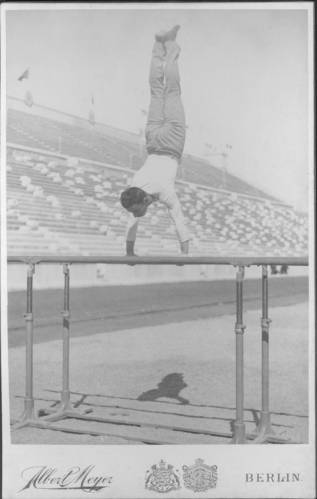

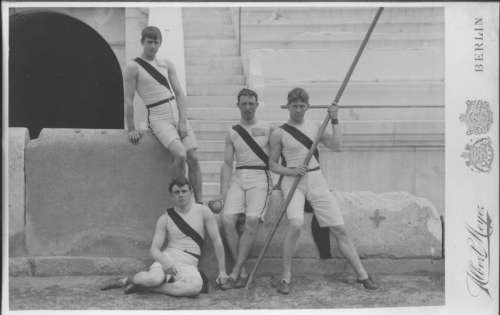

Needless to say that the various contests were held under amateur regulations. An exception was made for the fencing-matches, since in several countries professors of military fencing hold the rank of officers. For them a special contest was arranged. To all other branches of the athletic sports only amateurs were admitted. It is impossible to conceive the Olympic games with money prizes. But these rules, which seem simple enough, are a good deal complicated in their practical application by the fact that definitions of what constitutes an amateur differ from one country to another, sometimes even from one club to another. Several definitions are current in England; the Italians and the Dutch admit one which appears too rigid at one point, too loose at another. How conciliate these divergent or contradictory utterances? The Paris Congress made an attempt in that direction, but its decisions are not accepted everywhere as law, nor is its definition of amateurship everywhere adopted as the best. The rules and regulations, properly so called, are not any more uniform. This and that are forbidden in one country, authorized in another. All that one can do, until there shall be an Olympic code formulated in accordance with the ideas and the usages of the majority of athletes, is to choose among the codes now existing.

It was decided, therefore, that the foot-races should be under the rules of the Union Frangaise des Sports Athletiques; jumping, putting the shot, etc., under those of the Amateur Athletic Association of England; the bicycle-races under those of the International Cyclists' Association, etc. This had appeared to us the best way out of the difficulty; but we should have had many disputes if the judges (to whom had been given the Greek name of ephors) had not been headed by Prince George, who acted as final referee. His presence gave weight and authority to the decisions of the ephors, among whom there were, naturally, representatives of different countries. The prince took his duties seriously, and fulfilled them conscientiously. He was always on the track, personally supervising every detail, an easily recognizable figure, owing to his height and athletic build. It will be remembered that Prince George, while traveling in Japan with his cousin, the czarevitch (now Emperor Nicholas II), felled with his fist the ruffian who had tried to assassinate the Jatter. During the weight-lifting in the Stadion, Prince George lifted with ease an enormous dumb-bell, and tossed it out of the way. The audience broke into applause, as if it would have liked to make him the victor in the event.

The bicycle match took place in the Velodrome which had only recently

been erected in New Phaleron.

Jury : Foreman : H. R. H. the Crownprince, Members : M. Mavros,

M. Ipitis, M. Waldstein, M Fabens. Ten competitors took part in the match,

three Greeks amongst them. M. Colettis, M. Constantinidis, and M. Aspiotis.

The distance of the race was to be 100 Kilometres, that is the cyclists

had to make 300 times the circuit of the track. The interest of the Public,

very great at first, fell off after a little while, for the spectacle of

seeing the cyclists whirl by at full speed became rather monotonous. The

weather on that afternoon was anything but mild ; a bitterly cold wind

blew across the plain and whirled up the dust inside and outside the enclosure,

whose low walls afforded hardly any shelter from the severe blasts.

Source document: Official Report 1896

At three o'clock the King appeared accompanied by his sons and by

Alexander, King of Servia, who had arrived the day before at Athens. The

race was kept up for a considerable time, till one by one the competitors

gave up the contest with the exception of Mr Flamand, a Frenchman and Mr

Colettis, a Greek. Once Mr Flamand had a fall, happily without coming to

grief, and for all that he reached the goal first, having made three hundred

times the circuit of the track, in 3 hours 8 minutes and 19 1/5 seconds.

M. Colettis was only 11 times behind him. The French flag was immediately

hoisted. The victor, who was thoroughly tired out after the race, received

quite an ovation from the enthusiastic crowd. His Majesty himself congratulated

both champions on their success. In the evening on account of the weather

there were less people parading the streets, than on the two preceding

days, though the town was brilliantly lit up and continued to be so during

the whole time of the Olympic Games.

Source document: Official Report 1896

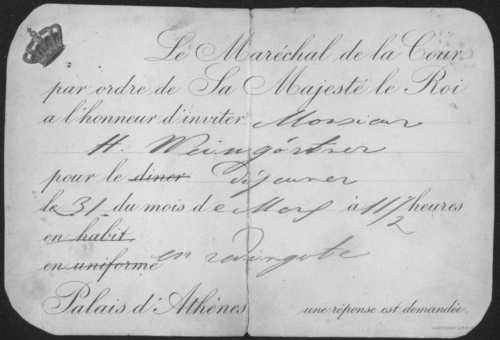

Every night while the games were in progress the streets of Athens were illuminated. There were torch-light processions, bands played the different national hymns, and the students of the university got up ovations under the windows of the foreign athletic crews, and harangued them in the noble tongue of Demosthenes. Perhaps this tongue was somewhat abused. That Americans might not be compelled to understand French, nor Hungarians forced to speak German, the daily programs of the games, and even invitations to luncheon, were written in Greek. On receipt of these cards, covered with mysterious formulae, where even the date was not clear (the Greek calendar is twelve days behind ours), every man carried them to his hotel porter for elucidation.

In the Spring of 1893, the situation was so far improved that a congress

could be convoked. We were on good terms with Belgium, England and America,

an invitation therefore was addressed to all Sporting Societies in the

world asking them to send delegates to Paris, during the month of June

1894. I called to my assistance such personal friends as Professor Sloane

of Princeton University, or gentlemen with whom I had been

corresponding on that subject for a long time, like M. Kemeny from Hungary,

General Boutowski from Russia, Mr Herbert from England, Commander Balk

from Sweden.

Source document: Official Report 1896

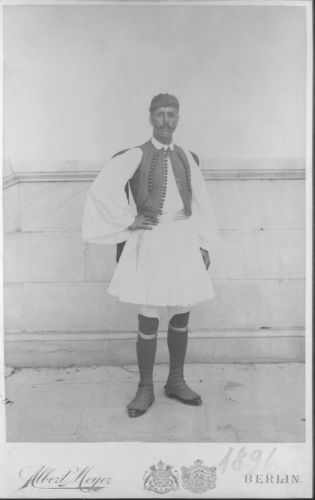

>On the same day the King had given in honour of the champions, who

had taken part in the games a great breakfast party. The members of the

International Committee, those of the Greek Committee, and its various

Sub - Committees, all the competitors, the representatives of the Hellenic,

as well as of the foreign press, in short all those who had in some way

contributed to the success of the games, two hundred and sixty guests in

all had received invitations to the Royal table. It was specially mentioned

in the invitation that the guests were requested not to make any change

in their usual attire, thus an American availed himself of this permission

and appeared in a bicycle suit, knickerbockers and short jacket. The Hungarians

alone wore the orthodox suit of black. Louis wore his national costume;

he was the object of general attention; his father, a kindly old peasant,

whose proud simplicity reminded one of Diagoras of Rhodes, had accompanied

him.

At 10 o'clock the King made his entrance, he wore, as usual, an admiral's

undress uniform. Immediately on his arrival the music of the Philharmonic

Society of Corfu struck up the National Hymn and then played the Cantata

of Samara. After having acknowledged the respectful salutations of his

guests, the King took his place in the centre of the long table, Prince

George sat on his right, Prince Nicolas on his left. Opposite sat H. R.

H. the Crownprince having on his right M. Zaimis, president of the Chamber

of Deputies, and at his left M. Scouzes, minister of Foreign Affairs, both

gentlemen had been members of the Council of Twelve. The Queen was unfortunately

not well enough to grace the breakfast with her presence. When the dessert

was put on the table the King rose and turning to the foreign representatives

pronounced in French the following toast:

"Permit me, gentlemen, to express to you the pleasure we all have

felt in seeing you come to Greece in order to take part in the Olympic

Games. By the warm welcome the people have given you, you have been able

to judge for yourselves with what joy the Hellenic Nation has received

you. I therefore seize this opportunity to tender my warmest congratulations

to those gentlemen, who have been victorious in the contests and I thank

you all for coming here. In a few days you will bid us farewell to return

to your respective homes. I wish you all good luck and good speed, I beg

you to keep us in good remembrance and I hope you may never forget the

emotions you shared with us, when the victor of the Marathon Race entered

the Stadion. I am sorry that the Queen is ill and cannot therefore, to

her great regret, be here to-day; she wishes me however to bid you welcome

in her name. Gentlemen, I drink to your health, in thanking you again most

sincerely for having come to Athens for the inauguration of the First International

Olympic Games.

This toast of the King was greeted at its conclusion by lively cheering,

in many languages.

Source document: Official Report 1896

Many banquets were given. The mayor of Athens gave one at Cephissia, a little shaded village at the foot of Pentelicus. M. Bikelas, the retiring president of the international committee, gave another at Phalerum. The king himself entertained all the competitors, and the members of the committees, three hundred guests in all, at luncheon in the ball-room of the palace. The outside of this edifice, which was built by King Otho, is heavy and graceless; but the center of the interior is occupied by a suite of large rooms with very high ceilings, opening one into another through colonnades. The decorations are simple and imposing. The tables were set in the largest of these rooms. At the table of honor sat the king, the princes, and the ministers, and here also were the members of the committees. The competitors were seated at the other tables according to their nationality. The king, at dessert, thanked and congratulated his guests, first in French, afterward in Greek. The Americans cried « Hurrah!» the Germans, « Hoch!» the Hungarians, «Eljen!> the Greeks, « Zito!» the French, «Vive leRoi!» After the repast the king and his sons chatted long and amicably with the athletes. It was a really charming scene, the republican simplicity of which was a matter of wonderment particularly to the Austrians and the Russians, little used as they are to the spectacle of monarchy thus meeting democracy on an equal footing.